Having and working toward goals is vital for success in school, work and life. Effective goals can motivate students to work hard, change their behaviors and focus attention on what really matters to them as they envision their own futures. But it’s much easier to say you have a goal than it is to work toward and reach one. People aspire to many things that they say they want, but they never really work toward. For example, students may say they want to go to a competitive college, but then not take the actions and reach the milestones that will actually help them get there.

As the school year begins to wind down, it’s a good time to encourage students to reflect on their goals for their summer and the near future. What do they really want, in the short- and long-term? What steps will they take to get there? How will they deal with obstacles and setbacks?

This article presents research-based approach to setting goals called WOOP (Wishes, Objectives, Obstacles, Plans), which helps students set realistic goals, envision success and deal with obstacles that come up. And it shows how teachers, peers and parents can all help kids be successful in working toward their goals.

— Kent Pekel, Ed.D.

President and CEO, Search Institute

The Importance of Goal Setting

Goals are simply statements of what we intend to do. Setting goals is a critical part of student motivation and achievement that has been studied since the mid-1960s. Setting goals provides a focus for managing or changing behaviors or how we spend time. Key findings across numerous studies and contexts include the following insights:

- Goals are necessary for judging competence and defining success and failure in many endeavors.

- Having specific, challenging goals boosts performance in goal-related areas.

- If goals are so challenging that failure seems probable, they are not motivating.

- Consciously setting goals makes it more likely that people will take actions toward those goals.

- Determining how to overcome obstacles in advance improves self-discipline and performance. A review of studies of goal-setting estimated that employers could increase productivity by 10 percent if they helped workers set realistic, specific, but difficult goals. Might the same be true for student achievement?

Three Parts of Goals for Behavior Change

By itself, goal setting will have little impact. Research on goals and behavior change identifies three aspects of goals that, when combined, lead to behavior change or learning:

- Setting goals, which provides a focus for learning or behavior change. Goal setting includes both the goal itself (what you want to achieve) as well as what you will do to lead to the goal. Specific, short-term, measurable goals are more likely to be acted on and, therefore, lead to change or learning.

- Problem solving involves identifying strategies for overcoming barriers to desired goals as well as dealing with setbacks that come up. This isn’t a one-time activity, but an ongoing part of working toward goals.

- Goal review involves monitoring and assessing progress toward a goal. Simply monitoring behavior (such as wearing a pedometer to track daily steps) can reinforce the desired activity. Goal review can also include checking in with others for accountability and support.

How Goal Oriented Are Youth?

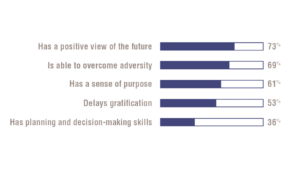

A gap often exists between young people’s future goals and their planning skills to “get there.” A survey of 122,269 middle and high school students by Search Institute found that many young people have a positive view of the future, believe they can overcome challenges, and have a sense of purpose. Yet they lack planning and decision-making skills, and they don’t consistently delay gratification for something they really want.

Goal Setting: Not Just a Rational Process

Sometimes the “teen brain” is characterized as being less developed, which leads to riskier behaviors. However, recent brain research suggests that the teen brain is more accurately thought of as being more flexible. It allows young people to adapt more quickly to changes in themselves and in the world around them. This flexibility makes it more open to exploring and adjusting to achieve goals, particularly if young people are motivated to do so.

Often the strongest motivations are more short term and grounded in their relationships and feelings. If we can tap into these motivations, we can cultivate “enduring, heartfelt goals” that are tied to young people’s core values and attitudes. Researchers illustrate the point this way: “Individual differences in the tendencies to be kind, honest and loyal in a romantic relationship may have as much to do with one’s feelings about these values and the consciously weighed decisions about the consequences of such behaviors” (Crone & Dahl, p. 647).

Motivating Goals: Are We Missing the Mark?

Common understandings of school success sometimes interfere with students setting goals that motivate them to learn. We typically think of school success based on comparisons (e.g., class rank), evaluation or performance (e.g., grades), or ability goals (e.g., test scores). These are called “performance goals.”

We’re less likely to think of school success based on task goals, learning or mastery goals. These would include goals about becoming more knowledgeable, getting better at something or learning to satisfy curiosity. These are called “mastery goals.”

But this emphasis on “performance goals” tends to be counterproductive. Most positive motivation and learning occurs when schools emphasize mastery and understanding more than competing for grades. For example, middle schools that promote a “mastery learning” focus tend to have students who have more academic self-efficacy. In the end, that leads to better grades (even though that’s not the focus).

Whether students are motivated by performance or mastery is not just a matter of an individual’s makeup. Rather, it is greatly influenced by the dominant approach in the school. If teachers create a culture that emphasizes mastery, students respond accordingly. In reality, of course, most tasks include some mix of mastery and performance goals. The question is about which goals are emphasized.

Indulging or Dwelling

People, including students, tend to set and work toward goals in two problematic ways:

Indulging

This approach involves imagining all of the good things that could come from achieving a goal, but not identifying any of the barriers that might get in the way. This approach reduces the effort put into achieving the goal, because they have skipped over what it takes to get there.

Dwelling

This approach involves focusing only on the obstacles, without paying much attention to the benefits of achieving the goals. These people lose motivation to work toward the goal.

When the benefits of achieving a goal are considered along with the obstacles, the resulting mental contrast increases the chances that the person will achieve the goal. In this approach, people become realistic optimists as they pursue their goals in life.

Positive Goals Matter, Even in the Face of Challenges

It can be challenging to focus on goals and the future when you’re not sure you have one — or that the future will be positive.

For some young people, the future doesn’t seem positive because of personal issues such as depression, mental illness, addictions or a major loss. In some cases, negative experiences or choices in the past limit options for the future.

For others, the future doesn’t seem positive because of community or social challenges, such as poverty, institutional discrimination, neighborhood violence and limited opportunities.

Yet, even in these cases, a focus on a positive future can be a powerful resource to motivate and guide choices. To be sure, the goals may be different. For example, young people may focus on how to adapt and navigate in the midst of adversity. Thinking about a positive future can help with motivation, coping, adapting and, potentially, connecting with others to improve the situation together.

One study found, for example, that working with juvenile offenders to think about their future selves had potential to help them think specifically about how they might turn their lives around, even though they had difficulty developing a concrete, positive vision of their future selves.

Supportive Relationships

Students don’t work on goals in a vacuum. The people around them — peers, parents and teachers — can either motivate or de-motivate them to work on and achieve our goals. They do this by:

- Reinforcing or undermining students’ self-confidence;

- Increasing or decreasing the perceived value of achieving the goal (including disagreeing with a young person’s goal); or

- Placing obstacles or distractions in the way of achieving the goal. Having friends, teachers and family members who are reinforcing the goal can be a big help. In addition, maintaining warm relationships can increase young people’s self-confidence in general, freeing them to focus on achieving their goals, not worrying about their relationships.

Setting and achieving goals is a complex challenge. Success is shaped by who we are, the goals we set, the strategies we use, and people who support us. Educators and parents can influence each of these elements to help young people take responsibility for their own growth and learning.

Personal Attitudes

For students to work hard on goals, two attitudes are important. First, they must value the goal. It must be something that’s important to them. If they don’t really value or see the benefit of the goal, they are much less likely to invest in it. Benefits may include positive feedback from others, prestige and the intrinsic value of achieving the goal.

Second, they must believe they can achieve it. If they are not confident in themselves or if the goal is too challenging, they will not be motivated to reach it — even if they see value in it. Sometimes they may be blocked from believing they can achieve it based on stereotypes or gender roles.

Meaningful and Challenging Goals

Moderately difficult goals tend to evoke more effort than goals that are too easy or too hard. Their reach (goal) should exceed their grasp (current ability), enough to feel like it is doable with effort, and enough that it will be satisfying and reinforcing when they do succeed. All truly motivating goals arise from some level of dissatisfaction with where one is currently. It is the dissatisfaction that creates energy for improvement, as long as the improvement goal is reasonably realistic.

Effective Strategies: The WOOP Process

WOOP is a research-based goal-management process (or self-regulation strategy) that helps people articulate their goals and the obstacles that stand in the way of reaching their goals. The WOOP process has been used in many areas of personal behavior change. The acronym WOOP stands for the major components:

Wish: Think of a wish or goal that is important to you but possible to achieve.

Outcome: Identify the benefits or best thing that could come from fulfilling the wish or goal.

Obstacle: Identify things that you have control over that could prevent you from fulfilling the wish.

Plan: Identify steps you could take to remove or overcome the obstacles. Adjust as needed.

In a small study, researchers found that using the WOOP approach significantly improved students’ grades, attendance and conduct. In another, students who practiced writing WOOP exercises completed 60 percent more practice exam questions than control group students.

Helping Students Set Goals

We know that students are most motivated when they set their own goals based on what is important to them. But teachers still play an important role in encouraging them to reach their goals. In addition to introducing the WOOP process to students, try these strategies to enhance their abilities to set and reach goals.

Connect with students.

Get to know what makes them tick and what motivates them. This understanding will help you coach them to identify goals that are meaningful to them. It will also boost their self-confidence when they believe they matter to you.

Give choices when making assignments.

This can increase the likelihood that they will be motivated to work on goals based on the assignment.

Coach them in setting goals.

Goals tend to be most motivating when they are specific, challenging and achievable. For example, a goal to “get better at” algebra is not terribly motivating. A goal to get 8 of 10 algebra problems correct instead of 5 out of 10 is easy to visualize.

Think out loud about strategies to achieve goals.

Encourage them to verbalize strategies for reaching their goals. (Saying it out loud helps students remember.)

Give specific feedback.

It shows that you are paying attention and that they are doing specific steps to make progress. “Good job” doesn’t explain why the student is moving towards a goal. “I like how you’ve broken that big assignment into small, doable pieces” would be better.

Help them create positive habits.

People are more likely to work on goals when there are cues in the environment that trigger the goal-related action. (A note on a mirror is a classic example.) This makes the actions more automatic or habitual, so you do them even when you’re thinking about other things.

Coach them in setting plans and priorities.

This planning includes not only what they intend to do, but also problems that might occur and ways of dealing with them. It also involves setting priorities for how to use their time so they can stay on track.

Recalibrate when needed.

Slip-ups will happen. They are part of the learning process. It’s important to help students learn from mistakes and setbacks, and then work to get on track toward the goal.

Celebrate milestones and achieved goals.

Positive feedback and celebrations to mark goal achievement reinforce students’ confidence and their motivation to pursue their next goals.

Jostens partnered with Search Institute to provide research-based data and advice for dealing with common school challenges. Over the past 30 years, Search Institute has studied the strengths and difficulties in the lives of more than five million middle and high school youth across the country and around the world to understand what kids need in order to succeed. Like Jostens Renaissance, Search Institute focuses on young people’s strengths, rather than emphasizing their problems or deficiencies. Visit SearchInstitute.org to learn more.

Click the button below to download and print the Getting Real About Goals guide which includes class activities, statistics and research around goal setting and the WOOP process.

WANT TO USE JOSTENS RENAISSANCE?

If you are a Jostens customer and you need a login to access all the resources on JostensRenaissance.com, email your rep or click here.

If you don’t currently partner with Jostens for yearbooks or graduation regalia or other celebratory products, you can learn more here.